Meta, the creator of Facebook and Instagram, recently introduced a new privacy setting that allows you to make a polite request—pretty please—for the company not to use your data to train its AI models. But does this new feature really provide the safeguard you're hoping for?

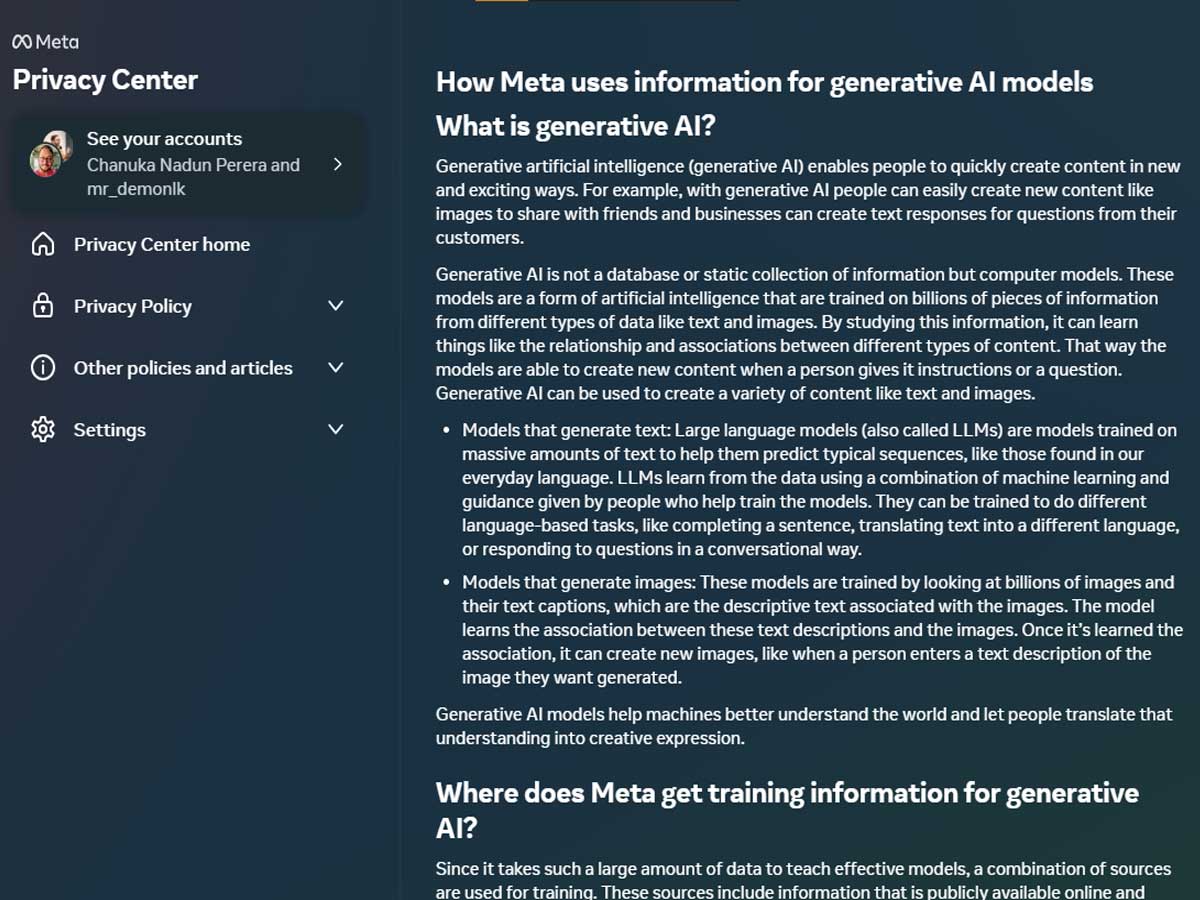

Tucked away in the recesses of Facebook's Privacy Center, a corner of the website most users rarely venture into, you'll discover an intriguing entry called "Generative AI Data Subject Rights." Here, Meta offers weary travelers a chance to submit requests concerning the use of their third-party information for training generative AI models.

Upon entering this enigmatic realm, you'll be presented with three options. You can request access to, download, or correct personal information. Alternatively, you can opt for the deletion of your personal data, or if your concern is unique, you can use a blank text box to detail your specific issue.

According to Thomas Richards, a spokesperson for Meta, the availability of these data subject rights varies depending on your location. Certain jurisdictions grant users the power to object to specific data being used for AI training.

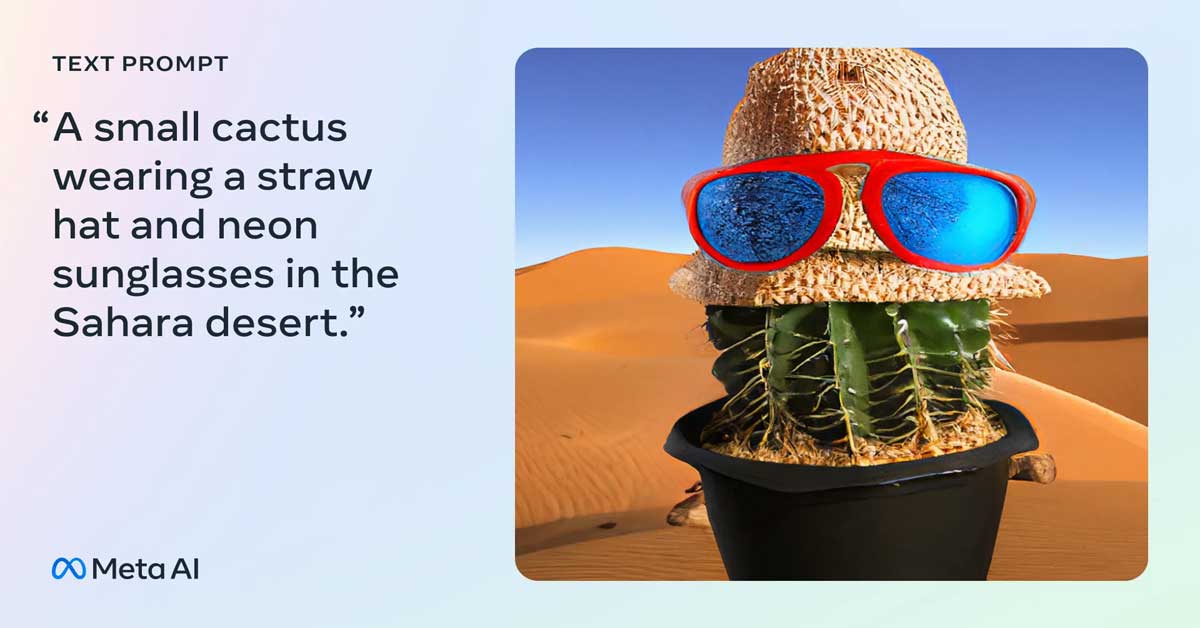

However, it's essential to note that as of now, Meta has not launched any generative AI features for consumers, and its Llama 2 open-source large language model was not trained on Meta user data. The company has, however, shared details about its AI approach in a previous entry within Meta's Privacy Center.

So, what does this form truly encompass? Does it empower you to protect the data you've entrusted to Meta's hands? It's essential to dissect the intricacies.

The model Meta is constructing and analyzing data from various sources. While some originate from the information you willingly input on Facebook, Instagram, and other apps, this form does not address this category of data.

The data you voluntarily shared within Meta's ecosystem remains under a different umbrella. While options to manage some of this data do exist, there's no straightforward way to object to its utilization for AI purposes.

The form primarily pertains to "third-party data," information acquired through scraping, purchase, or licensing from external sources.

When you submit your name and email through this form, the subsequent steps taken by Meta need to be clarified. Presumably, an automated search sifts through the training data for generative AI models in search of exact matches.

However, even if we assume the utmost rigor in this search, it's unreasonable to assume that data referencing you solely contains your full name or email address. Richards explains that the form's criteria are intentionally limited to name and email to minimize the amount of information shared.

Many individuals harbor a moral unease about corporate entities amassing data about them, processing it through opaque algorithms, and then releasing it through unpredictable AI. But does this moral objection translate into legal rights? In only a few jurisdictions do laws explicitly govern AI and privacy.

That's why the form asks for your country of residence. Meta grants certain individuals limited rights to intervene with their data based on their location. In some regions, Meta may have a regulatory obligation to do so, as "Data Subject Rights" under local laws confer the ability to delete, access, or modify collected data. For example, the UK and Canada enforce rules governing consumer data scraping, while the United States, at least at the federal level, lacks such regulations.

Richards emphasizes that submitting a request does not guarantee the automatic removal of your third-party information from Meta's AI training models. Meta reviews and responds to these submissions in compliance with local laws, recognizing that different jurisdictions entail distinct requirements.

Sources: gizmodo.com / facebook.com